Note: we are reposting a series of pieces written to accompany the ALA-funded Reading for Recovery Project. The following was originally published in the March 2016 issue of the Information Services News, Rutgers Center of Alcohol Studies

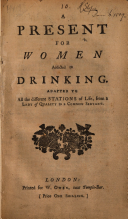

Author’s note: the following abridged essay is about a pamphlet published as A Present for Women Addicted to Drinking in 1750, also published in 1744 as An Epistle to the Fair-Sex on the Subject of Drinking. The pamphlet has been attributed to novelist Eliza Haywood, though a recent bibliographer finds the evidence for that attribution inconclusive; see Patrick Spedding, A Bibliography of Eliza Haywood (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2004), 634.

***

Only in the 19th century did the word “addicted” acquire the medical specificity it has today. Before this strong sense of chemical dependence it referred to any strong inclination, usually frowned upon––eighteenth-century Britons are described as “addicted” to judgmental gossip (in Samuel Richardson’s 1748 novel Clarissa), to swearing (in a 1759 open letter published in Dublin), and even to punning (in a 1716 London broadside). These are not joking analogies to the disease concept, like today’s “chocoholics” or “Netflix addicts”; addiction really was understood as just a characteristic habit, capable of encompassing everything from wordplay to tobacco. Even in the midst of the Gin Crisis, when cheap hard liquor found an alienated and dispossessed population with catastrophic results, writers didn’t yet have a fixed language for what made this vice more intractable than others.

The novelist Eliza Haywood’s 1750 pamphlet A Present for Women Addicted to Drinking should be understood as an attempt at such a language, not as evidence of a settled paradigm. The word “addicted” is tellingly among the smallest on the title page, functioning not as a positive diagnosis but as a stand-in for the still-hazy relationship between persons and their habits. Haywood’s “Present” to drinking women is more or less an intervention, a plea to those not too far gone to quit: “such as are barely touch’d therewith, rather through Custom or Compliance, than any Inclination of their own to so dangerous a Practice.” That gap between “Custom or Compliance” and “Inclination” is something Haywood keeps coming back to in different ways, trying to tease out where the point of no return is and why.

The novelist Eliza Haywood’s 1750 pamphlet A Present for Women Addicted to Drinking should be understood as an attempt at such a language, not as evidence of a settled paradigm. The word “addicted” is tellingly among the smallest on the title page, functioning not as a positive diagnosis but as a stand-in for the still-hazy relationship between persons and their habits. Haywood’s “Present” to drinking women is more or less an intervention, a plea to those not too far gone to quit: “such as are barely touch’d therewith, rather through Custom or Compliance, than any Inclination of their own to so dangerous a Practice.” That gap between “Custom or Compliance” and “Inclination” is something Haywood keeps coming back to in different ways, trying to tease out where the point of no return is and why.

The claim that there isn’t quite an addiction or disease concept here is not to say that Haywood puts physiology to one side. She does suggest a medical (or proto-medical) understanding of why one drink begets another: “The Habit of Drinking, as we every Day observe, entirely alters the Constitution, and at last brings it to such a pass, that the Evil becomes necessary, the very Nature of a hard Drinker being so entirely Changed by that pernicious Practice, as to become more akin to that of a Salamander, than of a human Creature, by deriving its Strength and Nourishment, not from simple and wholesome Nutriment, but from Fire and Flame.” The morally charged rhetoric, the belief that salamanders fed on fire, and the implicit Galenic concept of vital heat all mark the gap between Haywood’s paradigm and modern addiction science, but we can see here an interest in how addiction changes the relationship between the addict and the substance, turns a toxin into a necessity and an escape into a prison.

This general trajectory is laid out early on, and the rest of the pamphlet consists of variations on the theme: representative examples of how women of every class and marital status might succumb to drinking and the particular dangers it holds for each. (The question of why she targets women only is an interesting one for another piece!) The social cataloging is relatively encyclopedic and exhaustive. For instance, in the section on single women “The Daughter of a rich Tradesman” is followed immediately by “the Daughter of a middling Tradesman” and “the Daughter of a common Tradesman”; the section on married women repeats the same formula for wives.

Reading these in quick succession is a strange experience: drinking is represented as uniquely and especially dangerous for each group, to the point that the document as a whole starts to seem almost internally inconsistent. This is a Lake Wobegon approach to public health, where everyone’s vulnerability is above average. But reading it in this way might be a mistake. Instead of a sociological survey, this is really a series of character sketches ––and the profile of each character emerges from her characteristic vulnerabilities and temptations. The hope is that readers will recognize themselves, and Haywood’s taxonomy, comprehensive as it may seem, is hence open-ended: “Discourses of the same sort,” she tells anyone planning an intervention, “with proper Variations, according to the Circumstances, Age, and Quality [i.e. social status] of the Person, must be used, in order to reclaim any who have fallen unaware into this pernicious Custom.” To take it one step further, if drinking is a habit that comes to define particular characters, then recovery means both identifying with those characters and forging a new character for oneself by different habits. The inertia of recovery, Haywood hopes, might even come to mimic that of the decline. “As this Vice strengthens by Practice, so the contrary Virtue may also be rendered a Habit,” she writes. It’s worth noting here that “habit” has the double sense in this period of a repeated action and a characteristic garb (like a nun’s habit). Changing one’s habits starts with assuming a sort of habit; or, to put it more plainly, changing one’s character starts with assuming a character, identifying with a character.

What Haywood is advocating for might even be considered a sort of distant cousin to the Library’s Reading for Recovery (R4R) project. R4R, like A Present for Women Addicted to Drinking, offers stories––fiction, non-fiction, and everything in between––as a way of working through the issues of addiction and recovery. We don’t follow Haywood’s strict classification by “Circumstances, Age, and Quality,” but we do aim to provide people with situations they can relate to, opportunities to recognize something of themselves in what they read. The works we curate are more complex and idiosyncratic than her broad-brush cautionary tales, but we share her focus on addiction as a kind of form, the way it interacts with and shapes both characters and plots. In fact, the goal of R4R is something like that of Haywood’s Present as a whole: to think seriously about what addiction is and how it works, and to use narrative as tool of recovery.

–Originally published in the March 2016 issue of the Information Services News, Rutgers Center of Alcohol Studies, abridged version.

–For a longer look at the literature of the eighteenth-century “Gin Craze,” including this pamphlet, see Nick’s forthcoming article in Eighteenth-Century Fiction 33.3 (Spring 2021).