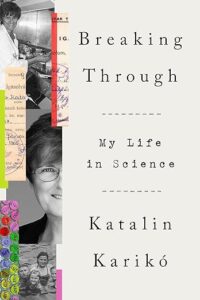

Breaking through: My life in science, a modest and unpresuming title, sounds unlike the typical editorializing titles of memoirs published by “celebrities” in the popular culture sense of the word. However, the world has learned the author’s name quickly in the past few years. Katalin Karikó is one of the exceptional scientists whose research on messenger RNA literally saved millions of lives in the recent outbreak of a worldwide pandemic: COVID-19. Based on the technology she developed via extending her research and collaborating with immunologist Drew Weissman, their modified technology was crucial for the effective COVID-19 vaccines. Doctors Karikó and Weissman were the recipients of the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Breaking through: My life in science, a modest and unpresuming title, sounds unlike the typical editorializing titles of memoirs published by “celebrities” in the popular culture sense of the word. However, the world has learned the author’s name quickly in the past few years. Katalin Karikó is one of the exceptional scientists whose research on messenger RNA literally saved millions of lives in the recent outbreak of a worldwide pandemic: COVID-19. Based on the technology she developed via extending her research and collaborating with immunologist Drew Weissman, their modified technology was crucial for the effective COVID-19 vaccines. Doctors Karikó and Weissman were the recipients of the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

“Katalin Karikó’s story is an inspiration.”—Bill Gates

Unaware of the above statement on the publisher’s site, as a science librarian I chose this book for the same reason: to inspire STEM students and early-career researchers to never give up. The book’s main takeaway is that you should follow your instincts and, with eyes on the prize, soldier on while maintaining your integrity. I also chose this book, written by a fellow Hungarian living in the United States, because I’m proud of Katalin Karikó’s incredible accomplishments and can relate to many of her experiences.

Baggage without a tag

The American reader would be surprised or even appalled at the humble beginnings of those of us growing up in communist Hungary or in the Eastern Bloc. Little do they know that it also provided an intellectually rich environment, making up for the huge gaps in our upbringing, weather perceived or real. Additionally, the love and respect within family and friends that one learned at a young age is one’s “baggage” that didn’t need its own airline tag when someone, eventually, was able to make it over here.

Without reminiscing over a childhood stolen from my generation amidst pioneer camps and other ridiculous mandatory engagements, becoming “a well-rounded member of the society” as a goal drilled into us came with high expectations: playing a musical instrument, learning foreign languages other than Russian, excelling in some sports, and participating in activities that prepared young pioneers for real life. All of the above in addition to getting top grades at school, college-bound from age 6 on a special track, such as science, foreign languages or music.

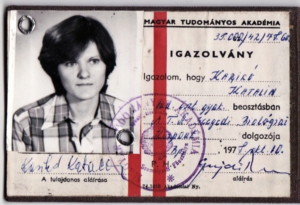

Staff ID, Szeged Center of Biology Research, Hungarian National Academy of Sciences. Image credit: Klebelsberg Library, University of Szeged, Hungary.

This is the background that defined Hungarian-born Nobel laureate Katalin Karikó, detailed in the first chapters about the early years of a Hungarian girl growing up in a small town. Surrounded by a supportive family and friends, her early interests in science could be easily fulfilled with a combination of studies, reading, and hands-on experiments. Coupled with her intellectual curiosity, talent and perseverance, her career trajectory forecasted a highly successful career as a scientist after earning her PhD. But not in communist Hungary.

When she was laid off from her research position, she was given an opportunity that very few scholars had in the Eastern Bloc: An invitation to become a researcher at an American university. Such a rare opportunity, one would say, but it was based on her scholarly achievements. It came with an exchange visitor’s J visa, allowing her to become a temporary non-resident alien in a vulnerable immigrant status. In the same boat but blessed with extraordinary bosses at Rutgers at the beginning, I was truly appalled to read about Kati (using her popular Hungarian nickname) trying to figure out Americans, including the “bossy” boss, and trying to decide whether it was typical or not to abuse the immigrant, to use power to get her deported or not extend the visa, which would put a quick end to her career.

Flying the nest

Mural in Budapest. Translation: “The future is written by Hungarians.”

My memory fails me. Was the foreign currency exchange limit per person $50 or still $5 when I was first allowed to get a “blue passport” to visit a “western” (i.e., non-bloc) country? An entire family was rarely issued blue passports to make sure that there was a member remaining in Hungary to return to. For Kati Karikó, to fulfill an invitation to the United States to work as a researcher was somewhat out of the ordinary in the mid-1980s.

Not unheard of is how she was treated in her research institution in Hungary, when she was first let go. Since I had the opportunity to work with some brilliant minds as a librarian during that time, I recall the endorsements that young researchers needed to survive and succeed, including the strong support of a well-established researcher, who had to be a loyal member of the reigning party. It was an environment where one needed a formal letter of recommendation from a party member just to be admitted to a PhD program! All’s well if it ends well: The world still benefits from the original idea she rescued from her research in the form of the vaccine.

The immigrant experience

Tackling the difficulties of a language that one speaks, albeit not yet fluently, is a common obstacle for many immigrants. If one learned the language mostly from books (the only option at that time), the intonation and pronunciation of spoken English, the local use of idioms or concepts within a discipline would hit hard as confusing and frustrating, in addition to any cultural differences. But Kati Karikó wasn’t taken aback. As she puts it: “Besides, let’s face it: When hadn’t I been a fish out of water?”

Upon arrival, Kati and her family were lucky to make fast friends with Hungarians who lived in the US. Building bridges connecting the two cultures is a great help at the beginning and often lays the foundations to lifelong friendships.

With new friends or not, I bet all immigrants can relate to her very first impressions in the United States, the moments when expectation finally meets reality. “Once we arrived, I’d thought we’d have access to everything it offered. But now that we were here, I was beginning to understand: There were levels to America, destinations within destinations.” For the American reader, this might sound like an immigrant Karen speaking! To clarify, as immigrants, we don’t feel entitled to have it all, it’s just a reality check.

Another side of the immigrant story is unfolding in the book through her husband’s life. To help pay the bills, Béla Francia would take odd jobs at the beginning, and as a jack-of-all-trades who learned a lot of skills by doing them in Hungary, he quickly became very successful. His story also demonstrates a significant part of the Eastern European mindset. Find out how it works and make it better. Set the goal and figure out the way to get there.

Do you remember these rotary phones? Image credit: Fortepan/Urbán Tamás (1981)

For the average American, it’s probably also shocking to read about their 5-year-old daughter’s first transatlantic flight to spend the summer in Hungary. The reason was purely financial; it was significantly cheaper than American childcare. Actually, if you think about it, it was much worse than how it sounds today. Can you imagine to be able to make a phone call to your 5-year-old only once a week? Remember, we are talking about the end of the 1980s, when the COCOM list banning the import of high technology was still in effect. The embargoed items unavailable for Hungarian families included phones (landlines) and computers, a reminder how lucky we are to have the modern ways of communication nowadays.

Before anyone starts worrying about the little girl, two-time Olympic gold medalist rower Susan Francia inherited her mother’s perseverance and has found her way to the top too. My favorite chapter, “Susan’s mom,” is one of the most skillfully composed memoir chapters. Spanning a period from 1997 to 2013, the vignettes of Susan’s college years through her rapidly rising career in rowing take turns with details of Kati’s research, brilliantly balancing the technical parts in science and sports with the warm scenes from a close mother-daughter relationship.

Kati and the library

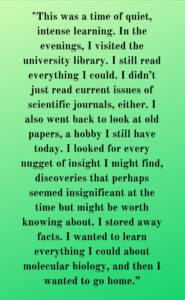

Click image to enlarge

I must admit that I was delighted to read about her extensive use of the library. At first, that tyrant of a boss of hers did not allow researchers to use daytime for anything else than precious lab work. Kati could visit the library after work only to be kicked out by the librarians at 11 PM. With her intellectual curiosity cranked up to 11, she enjoyed every moment of it (click on the image to enlarge quote on the right).

The reader today has no idea how time-consuming it was to find, read, save, collect, and organize articles without the fantastic electronic resources a library provides free of charge today. On top of all that, with very limited access to international print journals in Hungary (take it as a fact from me, the former librarian in a Medical School there). An American academic library must have looked like a treasure trove for Kati.

And then there’s more. One day, a wait for the photocopy machine resulted in a life-changing encounter as she entered into a conversation with a reserved, quiet fellow researcher. His name was Drew Weissman. The rest is history: they shared the Nobel Prize in 2023.

Now the University of Szeged, Hungary, has its Karikó Katalin Collection. Our Hungarian colleagues in the library at Kati’s alma mater curated an online exhibit (also available in English) to honor her achievements.

A non-fiction mystery

Reading about a series of unfortunate events in Kati’s life feels like reading a mystery abundant in plot twists, except that it’s a memoir, based on history and facts. One can’t make this up, I thought, as the details of her adventurous journey, with setbacks and failures over and over, unveiled in the next chapters, leading her from Penn to other institutions, only to end up back in Europe, while her family was always there to support her “obsession” that we call research.

As she explains it, ironically, her life followed “a similar pattern: a series of setbacks punctuated by moments of extraordinary breakthrough. The breakthroughs, for the most part, remained almost entirely invisible. The setbacks, though? Those were on full display.”

The message

Katalin Karikó, as most immigrants, received unsolicited advice all the time, including the infamous “stop talking to Hungarian colleagues in Hungarian,” implying we would never learn to speak English well (probably from a monolingual person who never left the state, let alone the country, if I want to be sarcastic, but it did happen to me).

As the winner of many prizes, awards, honorary doctorates, and popular votes, she is definitely in the right spot in her career to advise young researchers. Who wouldn’t love to have her as a mentor? Now we have her inspiring memoir as an alternative.

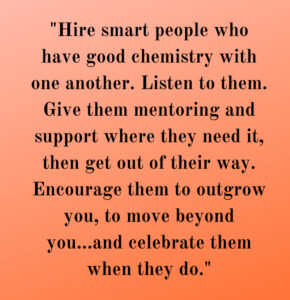

Click image to enlarge

In the book, the message is often attributed to others in her life, such as the role a principal investigator should assume (see on the right). The takeaway also comes in the form of thought-provoking questions based on her own experience, such as “how do we find the people who are out there right now, today, doing important work that is going unseen? How do we help get that work funded?” (referring to research in basic science, where the results don’t happen overnight and serious setbacks are part of the process). Her questions remind me that this memoir would be perfect for any book club, especially within academia.

As a librarian at an R1 university, I wholeheartedly support her suggestions to distinguish between “markers of quality science” and “markers of prestige,” such as job titles, citation counts, grants, service CV-lines, and the “dollars per net square footage,” a metric that worked against her all the time.

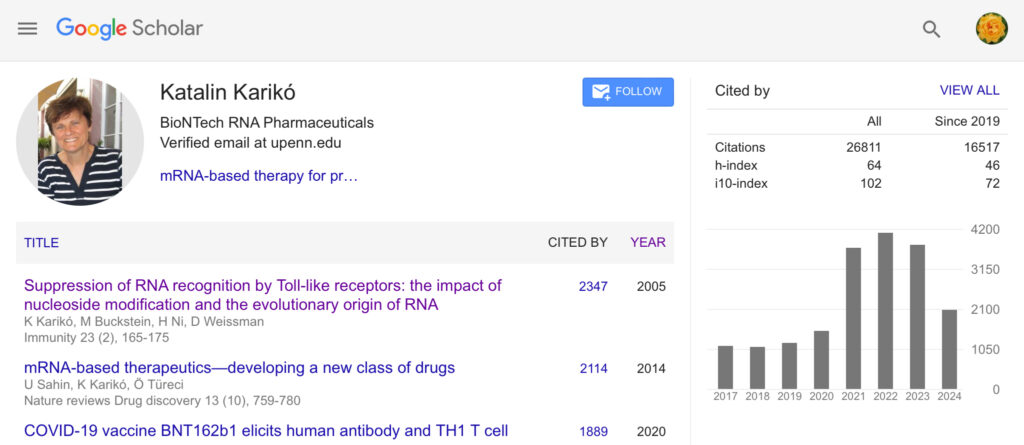

With its practical implications now clearly proven, Dr. Karikó’s scholarly output proves that valuable research might fall victim to current practices in academia. Published in the journal Immunity in 2005 (!), their landmark paper Suppression of RNA recognition by Toll-like receptors: the impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA barely got any attention. “It took a pandemic for the world to understand what we’d done and why it mattered,” she wrote. This article has been cited 2,347 times, as of today, according to Google Scholar. Karikó’s total citation count is now 26,811, with an h-index of 63, and the numbers have been going up!

Click image to visit Katalin Karikó’s profile in Google Scholar

From Rutgers University Libraries

Find autobiographies and memoirs written by extraordinary scientists in our collection. A few examples:

- Barres, B., & Hopkins, N. (2018). The Autobiography of a Transgender Scientist. MIT Press. – Known for his groundbreaking scientific work and for his groundbreaking advocacy for gender equality in science, a leading scientist describes his life, his gender transition, his scientific work, and his advocacy for gender equality in science a few months before his death.

- Ford, C. B. (2024). One way back: a memoir. St. Martin’s Press. – The true story behind the testimony of accomplished scientist Christine Blasey Ford before the Senate Judiciary Committee, which was considering the nomination of Judge Brett Kavanaugh to the United States Supreme Court that many of us followed glued to the live broadcast on September 27, 2018 in the library as she described an alleged sexual assault by the Supreme Court nominee.

- Gustafson, K. (2019). Reverberations of a Stroke: A Memoir. Springer International Publishing AG. – The story of mathematician Karl Gustafson’s Second Life: a near-death experience of his deep brain hemorrhage and his miraculous journey of recovery, an inspirational tale of grit and determination, in his own words.

- Jahren, H. (2017). Lab girl. Vintage Books. – One of the most popular science memoirs according to various lists and crowdsourced platforms on the Internet, the memoir is “an eloquent demonstration of what can happen when you find the stamina, passion, and sense of sacrifice needed to make a life out of what you truly love, as you discover along the way the person you were meant to be” (from publisher).

- Townes, C. H. (2023). How the laser happened: adventures of a scientist. Oxford University Press. – The ebook version of the memoir of a life devoted to science tells a story of another modest and quiet scientist, who was behind one of the biggest invention of the last century.