Matapris oli. The only sentence I remember from my one-semester course of an endangered Finno-Ugric language called Mansi, as part of the Master’s program at the Kossuth Lajos University (KLTE), Debrecen, Hungary at the end of the 1970s. To fulfill the requirements in diachronic linguistics, we had to pick one language from the Finno-Ugric language family. A language spoken by fewer than 1,000 people in the Soviet Union with no written resources seemed like a challenge.

The “textbook” was a so-called chrestomathy, a selection of texts assembled for the sole purpose of studying the language, along with a descriptive grammar, entitled Chrestomathia Vogulica, written by distinguished professor Béla Kálmán, one of the most recognized scholars in Finno-Ugric Studies. The Mansi language class was assigned to a young professor, Éva Schmidt, fluent in several of these endangered languages. So what?

The “textbook” was a so-called chrestomathy, a selection of texts assembled for the sole purpose of studying the language, along with a descriptive grammar, entitled Chrestomathia Vogulica, written by distinguished professor Béla Kálmán, one of the most recognized scholars in Finno-Ugric Studies. The Mansi language class was assigned to a young professor, Éva Schmidt, fluent in several of these endangered languages. So what?

It was the research on the background of our guest author, Natalie Díaz, that recalled these memories, as I discovered how passionate she is about preserving the Mojave language. As she puts it,

Language negotiates the way I know myself––what I believe I am capable of, how I know myself in relationship to others, what I can offer others, what I deserve from others in return. Language is where I am constructed as either possible or impossible.

Organizations and projects aiming to preserve endangered languages are not new to those with a background in linguistics. The Endangered Languages Project, the Living Tongues Institute, Wikitongues, Our Mother Tongues, and Glossika (with its Top 10 Universities to study them) are only a few. As someone from behind the Iron Curtain, I’d add the Endangered Languages of Indigenous Peoples of Siberia.

However, what’s even more interesting for me than the languages themselves are the individuals behind these organizations. Their passion, dedication, and oftentimes sacrifice involved in spending time at remote locations, collecting data in any way they can, recording and transcribing interviews, and then organizing and analyzing data, including miscellaneous field notes, into a pile that makes sense to be shared in a scholarly paper and, in the long run, to be used to revive a dying language (and its culture) via offering language classes for the community. As Díaz puts it,

Language is more than an extension of the body; it is the body, made of the body’s energy and electricity, developed to carry the body’s memories, desires, needs, and imagination.

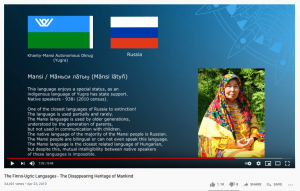

It was obvious to us that our Mansi instructor, Éva Schmidt, was somewhere on the spectrum of driven-obsessed-possessed. In a time when parts of the Soviet Union, such as the land of the Khanty and Mansi in Western Siberia, were strictly forbidden areas for foreigners (who needed a special pass just to leave Moscow or Leningrad) under severe penalty, she had still made several visits there with a friend from the community. In class, Éva not only talked about these field trips, but as she had actually learned the language from native speakers, she also shared some songs and poems in Mansi. (Or Vogul, as it is listed in my lecture book, in its given Russian name. And yes, the area in Siberia in which it is spoken also used to have a labor camp or gulag.)

Fast forward to 2021, one of the first pages that comes up in English is an Endangered Languages page listing Khanty resources, a publication dedicated to the memory of †Éva Schmidt. Just like that, with the symbol for the deceased.

When a word is silenced, what happens to the bodies who spoke it? What happens to the bodies once carried in those erased words?

A promising scholar with a PhD in Ethnography, she chose to walk the walk and relocated to live with the Khanty. Moreover, she founded the Folklore Archive of the Northern Ob-Ugric Peoples in Beloyarskiy in 1991 and trained others how to do field work, which resulted in the creation of other institutions. The emerging local scholarly community contributed directly to the active cultural revival of Ob-Ugric peoples in Khanty-Mansiyskiy Autonomous District. Before ending her life in a hotel at Khanty-Mansiysk in 2002, she blocked access to all her research with a 20-year embargo on her unique collection of recordings, artifacts, notes, and more, leaving her peers baffled ever since. Since little of Schmidt’s work was published in her lifetime, only next year when the embargo runs out will the world see her full legacy. She was a presenter rather than a writer, a walking encyclopedia, able to give an academic lecture on many topics in English and Russian in addition to her native Hungarian.

To lose a language is to lose many things other than vocabulary. To lose a language is also to lose the body, the bodies of our ancestors and of our futures.

Trying to make sense of the surrounding world and finding out who you are can take one to several paths. Reading and discussing texts others wrote is one, as is our practice at Books We Read. Conducting scholarly research on uncharted territories is another. Next is creative writing, and especially, writing poetry, offering others appropriate texts that they can relate to in their own ways, even if it’s just one sentence. Collecting and sharing songs, texts, customs, and traditions on the brink of extinction that exist orally in the first place will also help others make sense of the culture as well as discover and develop their ethnic identity.

When a verbal expression of love is crushed quiet, how long can the physical gesture of love continue in such oppressive silence? How can the gesture answer if nobody calls out for it verbally?

Listening to Natalie Díaz reading her poetry and conversing with Nick via his thoughtful questions at our author event on Wednesday was one of those long, unforgettable moments, probably the closest one can get to anything transcendental during a pandemic.

An authentic poet, Natalie Díaz helps us make sense, not only through creating a repository of the Mojave language resources, but providing a so-called “language event,” a relational experience, which is the foundation of getting in touch with our inner self to better understand ourselves in the world.

Classic bibliotherapy.

All quotes in the post are from Natalie Díaz in:

McCarty, T. L., Nicholas, S. E., Chew, K. A. B., Diaz, N. G., Leonard, W. Y., & White, L. (2018). Hear Our Languages, Hear Our Voices: Storywork as Theory and Praxis in Indigenous-Language Reclamation. Daedalus (Cambridge, Mass.), 147(2), 160–172.

Click to listen to spoken Mansi, the closest language to Hungarian.